Source: Government of Saskatchewan

Intensive Grazing

Intensive grazing describes livestock and grass management practices that focus on

- increased levels of manager involvement,

- increased forage quality,

- increased meat production per unit area; and

- more uniform forage utilization.

Managers practicing intensive grazing closely follow the interactions between plant, animal, soil and water. They determine where, when and what livestock graze, and control animal distribution and movement. They plan with these factors in mind, and this attention encourages positive attitudes toward the land.

Goal of range and pasture management

The goal of range and pasture management is to produce an optimum, sustained yield of livestock or wildlife while maintaining the land and watersheds in a healthy condition. Grazing systems are used to achieve this goal. Long-term successful grazing systems must do the following:

- Balance livestock numbers to forage supplies;

- Distribute livestock and grazing uniformly over the range, thereby reducing selective grazing;

- Provide adequate recovery periods for plant species;

- Maintain a healthy plant community and protect plants when they are most susceptible to grazing damage;

- Maintain healthy watersheds and soil;

- Meet the physiological needs of the animals;

- Optimize livestock gain per acre; and

- Be economically sound, practical to implement, simple to operate, and flexible.

Impacts of poor grazing management

Improper grazing management reduces plant tolerance to stress, cold, drought and disease.

Excessive defoliation results in desirable forage plants being replaced by less desirable species and reduction of surface litter levels, resulting in increased amounts of bare ground and risk of soil erosion. The water and mineral cycles cease to function efficiently and overall range and pasture productivity declines.

Livestock behaviour

An understanding of livestock behaviour is fundamental to recognizing problems associated with grazing. Animals are creatures of habit, using the same territories repeatedly, often leaving as much as 65 per cent of available pasture untouched. Livestock develop preferences for certain plant species and learn to become highly selective during grazing. They choose green leaves over stems and old forage. If given the opportunity, they regraze individual plants several times during the growing season, eating the succulent regrowth. These behavioural grazing preferences weaken the preferred forage plants.

Livestock show other behaviours that directly influence grazing. They are reluctant to use slopes exceeding 15 per cent, and in rolling terrain seldom graze at elevations greater than 70 metres above water. Grazing is also limited by the horizontal distance from water. Livestock rarely graze further than 2.5 km from water. They readily seek shade during hot summer periods, resulting in high usage of forested and riparian areas.

Controlling livestock behaviour improves animal distribution and plant use. Fencing, salt/mineral placement, herding, and water development are used to influence where and what animals graze.

Grazing systems control time, intensity and frequency of grazing on individual plants.

Principles of intensive grazing

Livestock, at high stock density, but not necessarily high stocking rate, are moved through the paddocks at a rate varying with plant growth and required recovery time. The goal is to evenly distribute livestock use and eliminate regrazing on individual plants.

The plant

Intensive grazing causes grasses to remain in the vegetative stage of development for a longer time period than under normal growth. This means, under favourable growing conditions, the plant produces greater amounts of green leaf area. Once a grass enters the reproductive stage, new growth is only possible through the activation of basal buds and development of new tillers.

Adequate regrowth is an important concept in understanding how the plant behaves under intensive grazing. It is best explained using two plotted curves that describe carbohydrate (or food storage) and overall plant growth.

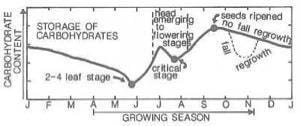

typical cool season grass plant. Carbohydrate

reserves reach a low point at the two to four leaf stage, and peak at seed ripe.

The carbohydrate storage curve shows seasonal fluctuations through the various development of phenological stages of a plant. Figure 1 shows how carbohydrate levels hit a low at the two to four leaf stage. Grass plants die if grazed repeatedly at this stage without allowing carbohydrate build-ups.

Root growth stops within 24 hours of severe defoliation. When moisture conditions are unfavourable, growth may not resume that season. This places the plant at a competitive disadvantage compared to other ungrazed plants in the sward. In general, leaving 50 per cent of the green leaf area will minimize the time period in which roots do not grow.

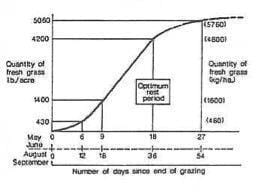

Andre Voisin, an early intensive grazing researcher, found that forage production follows a sigmoid or “S-shaped” growth pattern (Figure 2). He noted that growth was slow in the initial stages of plant growth, increasing rapidly during the central period and slowing again as leaves die.

a typical forage stand indicates how yield,

growth rates and rest periods change over

the growing season. (Voisin 1988).

Figure 2 Growth shows that the amount of time needed by an individual plant to recover from grazing varies with a number of factors. Significant and timely rainfall and/or temperatures will speed growth or regrowth, thus altering required recovery time. Conversely harsh conditions necessitate longer rest periods. Grazing intervals and rest periods must therefore be altered according to rate of growth which is in turn governed by environmental conditions and the vigour of the plant. Healthy plants recover most quickly.

Harvesting by livestock

Meat production is maximized when livestock can easily and quickly satisfy their appetite with high quality, abundant forage. For example, cattle achieve peak harvesting efficiency on dense forage that is 15 to 22 cm in height.

The Saskatchewan Experience

Tame pastures

The greatest benefits from intensive grazing management have been evident on tame pastures of crested wheatgrass (CWG), Russian wildrye (RWR) and meadow bromegrass. In addition to the close control of livestock grazing, fertilizers have been used to increase forage production and improve the leaf to stem ratio. Split application of fertilizers may be necessary because nitrogen (N) is often used within the first three weeks of spring growth.

Electric fencing

Electric fencing makes intensive grazing feasible. New types of electric fencing equipment are inexpensive, highly efficient, and can control large groups of livestock on very small paddock units. Livestock must, however, respect electric fencing. They must be trained to accept electric wire before going on to pasture. Also, the smaller paddocks and improved handling facilities associated with intensive grazing systems usually improve time and labour efforts.

Water sources

Water quantity and quality is often the limiting factor on the Northern Great Plains. Livestock need sufficient high quality water, or their forage intake and production declines dramatically. Fenced water sources eliminate tramping of reservoir banks, prevent fouling of reservoir water and prolong basin life. Use of water pipelines is an alternative that allows managers flexibility within their management plan.

Livestock Performance

Success with any grazing system depends on strict management, close attention to plant growth, and proper initial stocking rates.

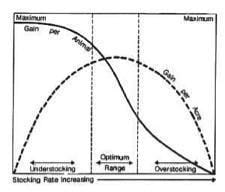

Relationship between stock density and meat production

stocking rate and production. Individual

animal performance is highest at a low

stocking rate and lowest when overstocking

occurs. Maximum gain per acre is achieved

at a moderate stocking rate.

The great challenge in grazing management is to optimize livestock production by establishing correct stocking rates and setting proper levels of use (Figure 3). It is well known that an individual animal maximizes gain when allowed to graze selectively at low stock densities. As stock density increases, the available forage becomes more efficiently used, and overall meat production climbs due to more animals and higher forage utilization of the stand.

However, there is a point above which overall production declines and the land becomes overstocked. Managers must watch their grazing lands closely and seek to maintain the delicate relationship between stock density and beef production.

History of intensive grazing

Intensive grazing is actually an old management practice. Nomadic herdsmen practiced intensive grazing by moving livestock from one range to another or by following seasonal forage supplies. Historically, these rangelands experienced prolonged rest periods that allowed the vegetation to fully recover and grow. Composition and productivity of the plant community remained sustainable under this kind of management.

In Britain and throughout Europe, intensive grazing practices go back over 500 years. Here, population pressures demanded greater productivity from the agricultural land base. The use of rotational grazing, tame forage species and fertilizer became established and accepted practices.

Early ranching enterprises in North America also practiced a form of intensive grazing management. Livestock, unrestricted by fences and property boundaries, moved as forage supplies depleted, and by default, the range received rest periods. However, as fencing use became widespread, season-long, continuous-use grazing became accepted. This produced many of the problems now associated with poor grazing management. Most livestock producers are taking advantage of the value of intensive management of livestock grazing management.

Conclusion

Intensive management of livestock grazing is not for everyone. Some producers find they spend an average of one and one-half hours per day monitoring grass growth, checking animals and making decisions on when to move livestock.

When implementing intensive grazing, try to:

- Start small. Don’t attempt too much initially. Begin with a small, manageable area, where you can afford to make a few mistakes;

- Talk to those who have practised intensive grazing;

- Read material about the practice;

- Learn to identify key forage species and decide which forage species to manage for;

- Plan well, but also ensure flexibility;

- Collect baseline information and monitor for changes.

Remember, each situation is different. Only you can decide what is best for your operation.

Definitions

- Animal Unit Month (AUM) – the amount of forage consumed by a 1,000 pound cow, with or without calf, in one month.

- Grazing system – the manipulation of livestock in a planned manner in order to accomplish a desired goal.

- Preference – selective grazing exhibited by animals when confronted with choices.

- Riparian Areas – The lushly vegetated zones in coulees and alongside rivers, creeks, lakes, sloughs, potholes, hay meadows and springs.

- Stocking rate – the number of animals on a unit area of land during a month or a grazing season. This is usually expressed in AUMS/acre or AUMS/quarter.

- Stocking density – the number of animals on a given area of land at a moment in time.