Source: Michigan State University Extension, Jerad Jaborek

When interacting with livestock, especially in stressful situations such as transportation accidents, being aware of an animal’s behavior and body language is important for everyone’s safety.

Accidents are undesirable or unfortunate events that occur unintentionally and can possibly result in injury, damage or loss. Accidents involving livestock are not planned and represent a stressful environment for the animals. Farmers and truck drivers transporting livestock do their best to provide the livestock a low stress trip to their next destination. However, accidents involving livestock can occur due to unforeseen consequences. As a result, the Michigan State University Extension Emergency Response to Accidents Involving Livestock (ERAIL) team aims to prepare emergency first responders, law enforcement officials and others who may be the first to the scene of an accident.

Like humans, livestock species have behaviors and their own body language that can be interpreted by the handler interacting with them to maneuver the animal safely and effectively. Livestock are considered prey animals, and for this reason, they may interpret some of our behaviors as a threat and react by defending themselves or trying to escape from such threats. This is the case of the natural “fight or flight” response.

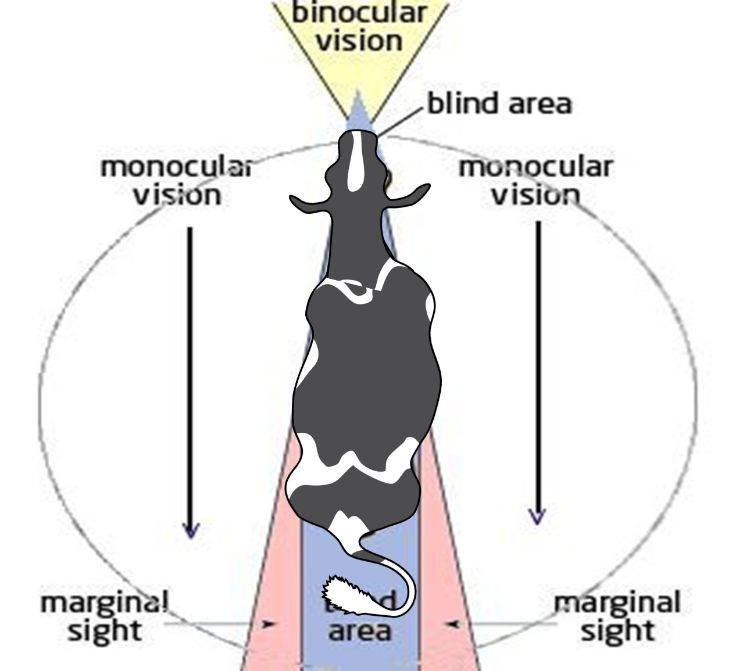

For many prey species, the location of the eyes are on the side of the head as compared to the front of the head for predator species. The advantage of eyes located on the side of the head allows for a greater field of sight, approximately 300 degrees, with a blind spot directly behind the animal (Figure 1). Additionally, much of the field of sight is monocular, with only a small portion being binocular vision in front of the animal, and another blind spot immediately in front of the animal. Due to the position of the eyes on the head of livestock (prey) species, there are a few animal behaviors and responses to be aware of when handling livestock.

When maneuvering livestock, you want to avoid standing in blind spots where the animal cannot see you. Standing in the blind spots of cattle and horses can startle them and provoke kicking as a defense mechanism. Standing slightly off to the side and out of kicking range is more ideal. Livestock handling tools that can act as an extension of your arm can help keep handlers safe from being kicked.

Since many livestock (prey) species also have a blind spot located directly below and in front of them, changes in elevation or flooring can present challenges when moving livestock. Often livestock may need time for leaders to drop their head and inspect the flooring/ground elevation change before proceeding. Additionally, light and shadow contrasts can prevent livestock from moving in the desired direction. Keep this in mind as livestock are moved into blinding light outside of trailers or into trailers that may be dark or poorly lit inside.

Using solid siding gates or panels can limit or obstruct the view of livestock and prevent them from being deterred by nearby distractions that they may be able to see (e.g., flashing lights, other people walking by, etc.).

Cattle, goats and especially sheep have a strong herd instinct. As prey animals, they find safety within the numbers of their herd and being isolated presents vulnerability that can be perceived as dangerous. Whenever possible, maneuver these animals in a group to help keep them calm. Keep in mind, if or when single animals need to be separated from the group, they may try to rejoin the group. In an attempt to rejoin the group, the separated animal may be willing to run through or past livestock handlers with force to regain safety within the group.

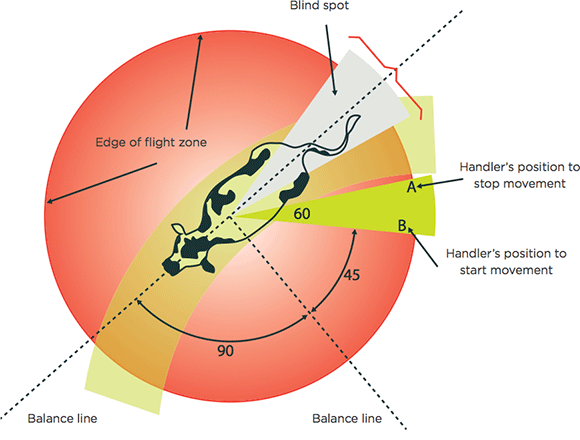

Much like people have a personal space that surrounds them, livestock also have a personal space that they prefer people do not enter called the flight zone (Figure 2). The size of the flight zone can differ for different livestock species due to their different past experiences and management. It is important to keep in mind during stressful situations like traffic accidents that the flight zone of livestock animals can increase. Applying pressure or entering the flight zone of an animal will cause them to move away from you. As animal handlers, we can couple this concept with the point of balance of an animal to get them to move in the desired direction.

The point of balance is around the point of the front shoulder of the animal (Figure 2). Standing in front of the point of balance will cause the animal to turn away and go in the opposite direction when the livestock handler applies pressure by stepping into the animal’s flight zone. When attempting to get the animal to walk away from you, stand off to one side and behind the animal, where the animal can still see you. Talking to them quietly also lets them know where you are in case they lose sight of you.

These animal behavior concepts affect the way we need to approach so we can handle animals safely and effectively at all times.

The Michigan State University (MSU) Extension ERAIL team is offering a training on Oct. 12, 2024, at the MSU Pavilion in East Lansing, Michigan, for those who respond to these accident events. The ERAIL training will provide attendees with a classroom presentation and resources, livestock trailer and ERAIL response trailer tours, as well as hands-on training with various livestock species. The Oct. 12 event is scheduled to have cattle, horses, pigs, sheep and honey bees present. Attendees will gain experience using livestock handling equipment to maneuver livestock and practice loading and unloading livestock from trailers. More details and registration information can be found by visiting ERAIL Training October 2024.